Low Back Pain

Low-back pain is an often debilitating, excruciatingly painful experience. Costing the UK economy millions of pounds each year in days lost through injury. The term ‘low-back’ pain can cover a multitude of symptoms and situations, this article will focus on how effective core conditioning can help protect the low back and prevent pain.

Structure of the Spine

The human spine consists of 24 separate bony vertebrae. Consisting of 7 cervical, 12 thoracic and 5 lumbar vertebrae together with 5 fused vertebra which form the sacrum. The spinal column has 3 main functions:

-

To support the human body in an upright posture

-

It allows movement and locomotion

-

It protects the spinal cord

Each one of these vertebra are a specific size and shape, forming two bends, one at the bottom (the lumbar) and one at the top (the thoracic) of the spine. The position of each vertebra allows excellent shock absorption during gait (walking, jogging or running).

From the lumbar portion of the spine the vertebrae are very large and get progressively smaller the higher up the spine we go. The lumbar vertebrae has limited mobility and as we look higher up the spine there is progressively more potential movement, allowing us to rotate more at the top then at the bottom. Between each vertebra (apart from between C1 & C2) lies a disc. The disc is made up of two parts. The outer section is called the annulus fibrosus which is relatively elastic and the inner section called the nucleus pulposus which is a semi-fluid gel.

As the nucleus pulposus is a fluid, it can be deformed under pressure without losing any volume. This essential property allows both movement and the transference of compressive load from one vertebra to the next. The exact position of the nucleus is not the same throughout the spine. It varies from being central in the thoracic spine to being positioned more posteriorly in the lumbar and thoracic regions.

How Muscles Effect Posture

Posture is deemed as the position from which movement begins and ends. Ideal posture allows our muscles to work with minimal resistance. Poor posture results in increased workloads for our muscles and an increased risk of injury and pain.

When a muscle contracts it becomes shorter, thus bringing the origin and the insertion of the muscle closer together and providing movement. Every muscle in our body has a ‘normal’ length and a ‘normal’ range of movement. Whilst this may differ from person to person slightly, the overall ranges are pretty consistent. If these ‘normal’ ranges are lost, posture will invariably be affected in some way. For example if the rectus abdominis becomes short and tight, the rib-cage will be drawn towards the pelvis thus causing a ‘slumped’ posture. As the centre of gravity shifts forward the head will also migrate forward. This can cause a ‘sheering’ at C7/T1, in an effort to offer support and stability to the area the body lays down extra tissue resulting in a dowager’s hump (an increased hump of tissue at the base of the neck).

So what causes these muscles to become tight?? The answer is many things can potentially cause muscular imbalances. The two most common causes however are through improper training techniques and through extended periods in a shortened position i.e. sitting at a desk for 8 hours a day!!

Posture & Pain

As discussed earlier, the vertebral column is constructed to allow stability and some shock-absorption. This mechanism is both mechanically sound and theoretically full-proof. However, Mother Nature did not count on our lives changing so drastically from hunting outdoors to fighting against a deadline in the office! We are becoming more and more sedentary with the majority of the workforce spending large portions of the day seated. This can cause some key issues for our bodies; 1. We are kinetic beings and are designed to move, being in a seated position for large portions of the day does not help the many systems within our bodies to function optimally and 2, Long periods in a seated position can cause adaptive shortening of our muscles, most notably the hamstrings, abdominals and neck muscles. The combination of these muscles getting shorter pulls the body into flexion and becomes the ‘normal’ position our bodies want to maintain. This alters the loading patterns for the neck and shoulder increasing the likelihood of tension headaches and neck pain.

Altered length of the hamstring muscles can be a major contributing factor to an increased risk of low-back pain. The hamstrings are found on the back of the thigh, it is a large muscle that is made up of 3 parts; biceps femoris, semitendinosus and semimembranosus. The origin of the hamstring is the ischial tuberosity (lower portion of the pelvis) and the insertion is a combination of points on the tibia and fibula (shin bones). The action of the hamstring is to flex the knee and extend the hip.

Short and tight hamstrings are extremely common in today’s sedentary high-tech world where we spend a large portion of our day sitting! As the action of the hamstring is to flex the knee joint, the muscle is naturally shorter when seated. Over time this can lead to adaptive shortening where the muscle no longer returns to its original length when standing or bending, this can have huge effects on our joints.

We are designed to have a slight anterior tilt in our pelvis, this aids the natural lumbar curve of our spine. The effect of short and tight hamstrings can be to reduce this anterior tilt and flatten our lumbar curve. This results in a reduced ‘buffer’ when we bend forward. With a normal range of movement as we bend forward our spine straightens slightly. This shift results in the fluid-like material of our disc’s being pushed posteriorly (backwards). In normal circumstances this is fine as the annulus fibrosis is strong enough to resist the force.

However, imagine the lumbar spine has lost some of its curvature through tight hamstrings. The ‘buffer’ is no longer there as the spine starts in a much straighter position and this curve is reduced further as we bend forward. The disc is likely to be exposed to higher and more frequent pressures then it is used to. Over time the fluid-like nucleus pulposus can start to wear away at the annulus fibrosis, like a bald spot on a tyre until the smallest pressure causes it to bulge and catch a nerve.

The inner-unit

Our body’s inner-unit provides stability and support. It offers a solid foundation to allow movement to occur. The inner-unit consists of four muscle groups that work together as a system; the TVA (Transversus Abdominis), diaphragm, multifidus and the pelvic floor. These muscles are all on the same neurological loop and help to stiffen the spine, pelvic girdle and rib-cage so the head, arms and legs have a solid working foundation. If your inner-unit ceases to function effectively you lose the ability to stabilise your core or extremities, drastically increasing the likelihood of injury. This is particularly common in the low-back, as without the support of the inner-unit the ligaments of the spine are over-worked.

The TVA (Tranversus Abdominis)

The TVA’s origin is the internal surfaces of ribs 7-12, thoraco-lumbar fascia and the iliac crest with insertion at the linea alba (connective tissue that runs down the mid-line of the abdomen). Its function is primarily to increase intra-abdominal pressure, for this reason it is a major stabilizer of the lower back.

The stability of the spine and lower extremities is created through the action of the TVA on the lower back and pelvis. When the TVA contracts it draws the belly-button toward the spine through a large piece of connective tissue (the thoracolumbar fascia) that is attached to the spine. This causes the bony prominences of the lumbar spine to be pulled upon from both sides at once, resulting in increased stability on both sides of the spine at once.

Through the action of the inner-unit this increased tension offers fantastic support and a solid foundation to move. This becomes particularly important when bending forward as our bodies shift from using our muscles to ligaments for control and stability. If our inner-unit is functioning well it offers support for the ligamentous system and helps to protect the low-back.

The Six-Pack Muscle

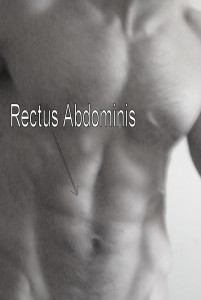

Our bodies possess both an inner and an outer unit. Our inner-unit provides us with the foundation from which to stand upright and to move. Our outer-unit is made up of the muscles that create movement. When people talk about our ‘core’ muscles they often refer to the ‘six-pack’ or Rectus Abdominis (pictured below).

The primary role of the Rectus Abdominis is to ‘flex’ the spine by bringing the rib-cage toward the pelvis or if the upper-body is fixed, the pelvis towards the rib-cage. It is an outer-unit muscle, therefore its ability to offer segmental stabilisation for the spine is poor. It can offer gross stability when working in conjunction with other muscles but to focus on this muscle when talking about ‘true’ core stability would be missing the more important parts.

Weight Belts

Weight-belts have been worn for many years by power-lifters. The reason for there rise in popularity is they offer stability when exerting heavy loads through the lumbar spine. The reason they can do this is they can create something called ‘intra-abdominal pressure’. This mechanism can alleviate between 12% and 36% of the load in the lumbar spine at the L4 and L5 levels. As the abdominals contract against the viscera (internal organs) they are pushed superiorly into the contracted diaphragm and inferiorly into the pelvic basin. The result is elevation of the diaphragm, which through its attachments to the L2 and L3 vertebra creates a de-compressive force.

So, weight belts must be a good thing right? Wrong, as discussed earlier when the TVA contracts it offers stability for the spine. Wearing a weight belt teaches the body a faulty motor pattern as the abdominals push out against the belt to create the intra-abdominal pressure. This pattern if repeated will become the norm, meaning any time the abdominals are called into action the belly-button will push out instead of being drawn in! This drastically reduces the spine’s support and stability, increasing the risk of a low-back injury.

Conclusions

In my own personal experience helping to correct posture and improve inner-unit function can have a profound effect on the prevention and management of low-back pain. By correcting muscular imbalances (such as tight hamstrings) and strengthening the ‘core’ muscles (specifically the TVA and lower abdominals) it can create a solid foundation from which we can move without pain.

Reference Material:

Oliver & Middleditch – 1991 – Functional Anatomy of the Spine

Fairbank J.C.T., O’Brien J.P. – 1979 – Intra-abdominal pressure and low back pain.

Paper read at Annual Meeting of International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine, Gottenburg, 1979.

Gracovetsky S., Farfan H.F., Helleur C. – 1985 – The Abdominal Mechanism

Gary A Thibodeau, Kevin T Patton -2003 – Anatomy & Physiology

Jurgen Weineck – 1986 – Functional Anatomy in Sports

Richardson, Jull, Hodges & Hides – 1999 – Therapeutic Exercise for Spinal Segmental Stabilization in Low Back Pain

James A. Porterfield & Carl DeRosa – 1998 – Mechanical Low Back Pain

James A. Porterfield & Carl DeRosa – 1991 – Mechanical Low Back Pain; Perspectives in Functional Anatomy.

Tesh KM, Dunn JS, Evans JH – 1987 – The Abdominal Muscles and Vertebral Stability. Spine. 12:501.

Paul Chek – 2004 – How to Eat, Move and Be Healthy